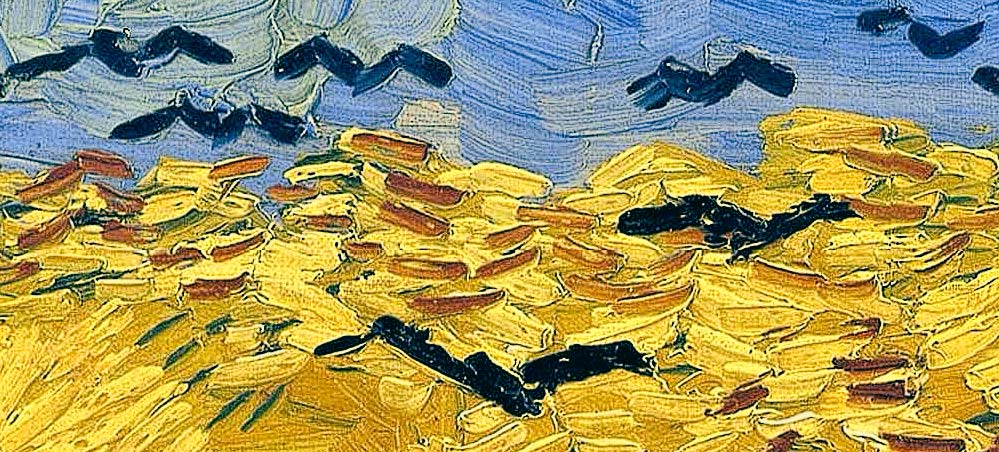

Allow me to add up what I’ve discussed thus far: the 2.5D digital paintings we today create onscreen will soon be capable of being 3D printed to reveal the thick impasto buildup depicted on the display. The key missing component currently preventing this is the ability to output a 2.5D digital painting in a format that a specialized 3D printer understands. Once a compatible file format is in place and a 3D printing service offers prints from user files, impasto style 2.5D digital paintings will be capable of being recast in the real 3D world.

I'm not suggesting that traditional oil painting is now irrelevant. But consider this: we tend to be comfortable with what we know. Change can be disruptive. Take a look at the invention of the automobile. The public initially dubbed autos a horseless carriage for the sake of familiarity. Another example is Greek temple architecture, whose original construction material was wood. As stone replaced wood building materials, the shapes of elements —columns and entablature, for example— remained the same.

In these and innumerable other cases, new materials have resulted in new forms. While it may be initially entertaining to recast an oil painting into a new medium, in the long term these mimicked forms will evolve beyond the limits of the older medium it imitates.

Advances in nanoscale science and engineering are already producing new classes of coloring materials that will eventually make their way into commercially available art materials, including paint and inkjet inks. These new colorants utilize structural coloration rather than dyes or pigments. The perceived color doesn’t arise from pigmentation, but from the light scattering off nanoscale structures embedded in its wings.